Italy, as widely known, is a land of saints, poets, sailors and, at least when talking about sports, team managers of the national football team.

It was always like that, at least until the morning of Monday, July 14, when all over Italy everyone forgot to discuss about football and started talking of tennis and plays such as ‘topspin forehand’, ‘stop volley’ and ‘slice serve’.

All thanks to the prowess of Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz, who in the Wimbledon final kept us glued to our TVs and smartphones for three memorable hours, with lightning-fast accelerations alternating with soft drop shots. And who knows if, from up there, Major Walter Clopton Wingfield will have been able to appreciate (or not?!) how the game he invented 150 years ago has evolved.

From patent to game: the birth of tennis

As in any success story, in fact, tennis was also born from an invention and the filing of a patent application with the British Patent Office, that Major Wingfield filed to protect a kit containing all the necessary gear (net, poles, balls and rackets) to transform any lawn in the English countryside into a court suitable for playing the new game known as ‘lawn tennis’: an open-air version of the older Royal Tennis.

The ‘new’ game would soon replace croquet, which was much loved by the British aristocracy at the time (think about Alice in Wonderland or Manet’s paintings), so much so that the famous All England Croquet Club quickly changed its name to the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, that is still the name of exclusive club “our” Jannik Sinner entered as an “Honorary Member” about a week ago by winning the world’s most popular and renowned tennis tournament: Wimbledon.

The game, then little more than a hobby with polite and graceful movements, has now become a global sport in which athleticism and powerful strokes are pivotal elements: but how did that happen?

Innovation. This is the key.

The revolution sets in with patents

René Lacoste, known to everyone for his famous polo shirts and only to the most passionate for his tennis career in which he boasts no less than 10 Grand Slam tournaments, actually contributed significantly to the development of the game also from a technical point of view. He designed ‘ball-shooting’ training devices, ancestors of ‘the dragon’ so hated by Andre Agassi in his childhood, and a slew of rackets, including the first metal-framed one, the rights to which (e.g. patent DE1195210 of March 30,1960) were then licensed to the US company Wilson Sporting Goods Inc., since then the world’s leading racket manufacturer.

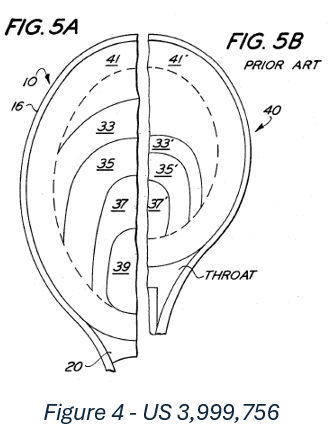

Or Howard Head, founder of the company of the same name (yes, that Head), but who became famous in

the racket world with another brand, after leaving the company that carried his name to move to Prince Manufacturing Inc. Here Head developed the first aluminium racket, patenting it on September 10, 1975 (US 3,999,756) and launching it on the market under the name Prince Classic.

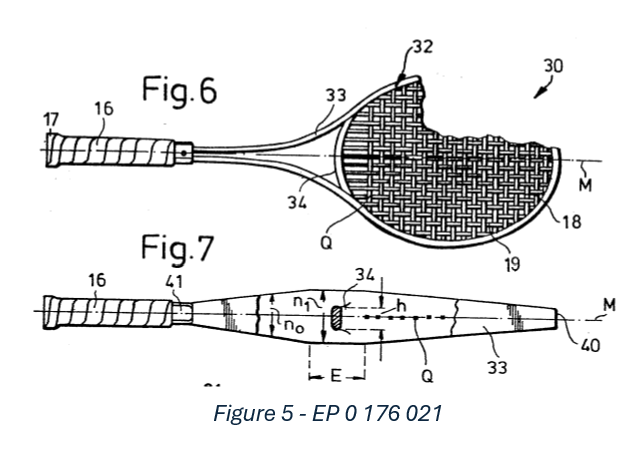

And then back to Wilson, which, having learnt Lacoste’s ‘lesson’, never stopped investing and searching for solutions to optimise the performance of its equipment, once again disrupting the market in the 1980s, after being granted the rights to exploit the invention from another brilliant inventor, certainly less known than Lacoste but with equally disruptive intuitions: Professor Sigfried Küebler, inventor and holder of several patents (EP 0 176 021 of September 22, 1984) that Wilson bought to develop the widely known ‘Kuebler Resonanz’, a racket allowing any Sunday league player, such as myself, to hit strokes of considerable power (for the accuracy further innovation is needed…).

Hi-tech balls and shoes for ever-greater performance

ut rackets are only one of the components. And the balls? The earliest patents date back to the beginning of the last century, filed by Dunlop, Spalding, Slazenger, up to the present day with Bridgestone, Wilson (again!) and Sumitomo.

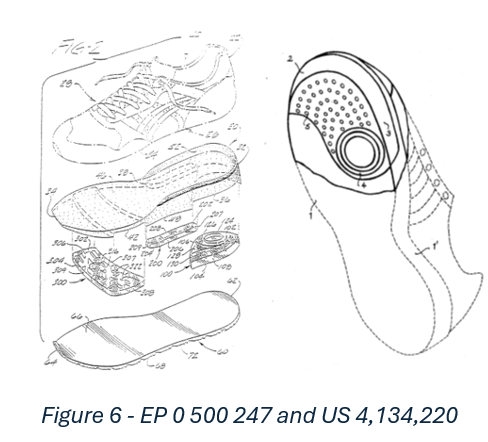

Or the shoes: those used by Fred Perry or Lacoste would not allow Sinner & Co. to sprint and glide around the court without suffering the consequences, but even in this field, technology and innovation, suitably protected, have supported, and perhaps even guided the evolution of the sport that today is undoubtedly among the most followed and practised in the world.

The ‘Wimbledon’ brand: when tennis becomes a trademark

All the protagonists of the ATP and WTA tours, as well as the major tournaments, have for years now been real trademarks, obviously registered, capable of conveying messages and marketing products of various kinds. Starting with the Wimbledon Tournament, for which, with great foresight, the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club registered the trademark back in 1884.

Invent, protect and innovate: game, set and match

From Wingfield to today, therefore, history teaches us that innovation (if protected correctly) can last. This is because a protected and safeguarded idea takes on a value that, if maintained and nurtured, then becomes the key to its success in any field, including sport.