This article first appeared in World Trademark Review magazine issue 79, published by The IP Media Group. To view the issue in full, please go to http://www.worldtrademarkreview.com

As the use of distinctive and non-traditional signs continues to evolve, EU legislation now allows for objects, actions and patterns to be registered as trademarks, with a key focus on trade dress

The evolution of distinctive signs in recent decades has resulted in a variety of source identifiers other than traditional signs (eg, word and stylised marks). As a result, the legislature across the European Union and worldwide has broadened the capability for objects, actions, events and patterns, among others, to be registered as trademarks. IP law literature and jurisprudence have already identified smell, sound, colours and packaging as source identifiers.

The latest developments on nontraditional trademarks focus on trade dress. In the European Union, there is no single way to protect product and packaging shape, product colour and shop

fronts. However, combining the more significant IP protection tools (mainly trademark and design) can be a useful way to protect trade dress.

Looking into the effectiveness and cost-benefit of protection, trademarks (in particular, three-dimensional (3D) marks) play a crucial role. Unlike designs, 3D EU trademarks enjoy the following advantages:

• They are renewable for an unlimited period.

• They protect a broader subject matter (the likelihood of confusion standards, typical of trademarks, apply).

• There is no matter of disclosure or prepublication to be considered.

In addition, the subjective viewpoint to consider when assessing similarity and invalidity for 3D EU trademarks is the ‘average consumer’ rather than the ‘informed user’ in that particular field of expertise.

Nonetheless, obtaining protection through the EU Community design registration is not as demanding as obtaining protection for EU trademarks from the EUIPO. As a result, in terms of regulation, the clear advantage of Community designs is that the heavy burden of proof on the grounds of distinctiveness is drastically mitigated by the easy-to-meet requirements.

3D marks as trade dress

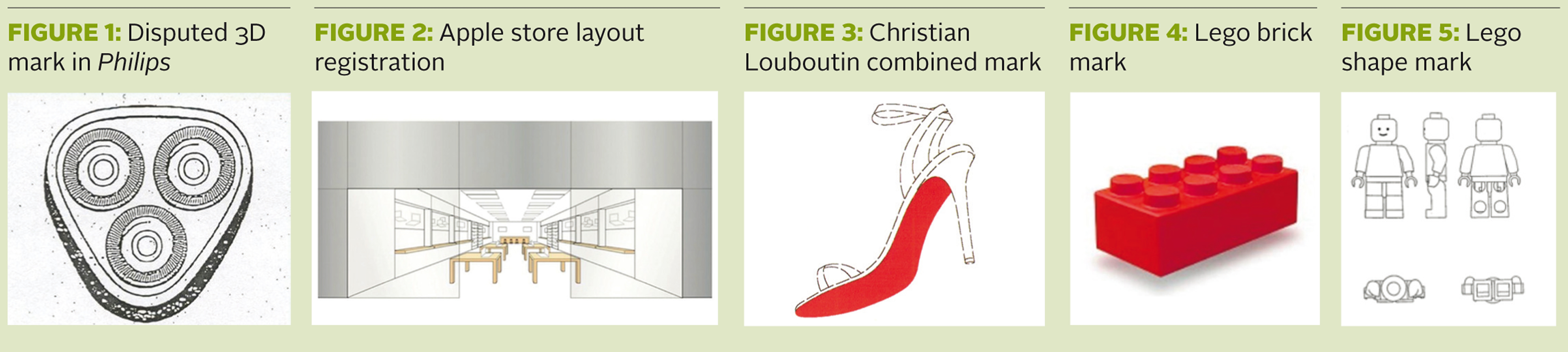

Philips v Remington (C-299/99) One of the first decisions of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) relates to a 3D trademark (see Figure 1).

On 18 June 2002 the ECJ issued a decision, in connection with the interpretation of Article 3(1) and (3) of EU Directive 89/104, to approximate the laws of the member states relating to trademarks, in particular 3D EU trademarks.

The decision highlights that only marks with a distinctive character by their nature or their use are capable of distinguishing the goods claimed from the goods of other undertakings and, as a result, are capable of being registered: “where a trader has been the only supplier of particular goods to the market, extensive use of a sign which consists of the shape of those goods may

be sufficient to give the sign a distinctive character for the purposes of Article 3(3) of the Directive in circumstances where, as a result of that use, a substantial proportion of the relevant class of persons associates that shape with that trader and no other undertaking or believes that goods of that shape come from that trader.”

Apple Inc v DPMA (C‑421/13)

Ten years on from Philips, the ECJ was dealing with more sophisticated issues when “the presentation of the establishment”, namely, the layout of Apple’s flagship store (see Figure 2), was at issue.

The ECJ confirmed that the layout of a retail shop has access to 3D trademark protection and set out the prerequisites.

Apple Inc was already the owner of a 3D US trademark for “retail store services featuring computers, computer software, computer peripherals, mobile phones, consumer electronics and related

accessories and demonstrations of products relating thereto”. When seeking an extension of protection in Europe, the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA) found the trademark was unable to function as a source identifier, defining the sign as a mere representation of the essential elements of a shop.

1 2 3 4 5

Unpersuaded by the DPMA’s reasoning, the DPMA Board of Appeal argued that it was a matter of deliberation by the ECJ to allow the flagship store to be a trademark per se.

The ECJ found that a representation “which depicts the layout of a retail store by means of an integral collection of lines, curves and shapes, may constitute a trade mark provided that it is capable of distinguishing the products or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings. Consequently, such a representation satisfies the first and second conditions referred to at paragraph 17 of this judgment, without it being necessary either, on the one hand, to attribute any relevance to the fact that the design does not contain any indication as to the size and proportions of the retail store that it depicts, or, on the other hand, to examine whether such a design could equally, as a ‘presentation of the establishment in which a service is provided’, be treated in the same way as ‘packaging’ within the meaning of Article 2 of Directive 2008/95.”

This decision has already changed the perception of 3D trademarks – and nontraditional trademarks in general – and has shaped the ambitions of trademark owners to broaden the concept of ‘non-traditional trademarks’ even in advance of recent EU trademark reform.

Christian Louboutin v van Haren Schoenen (BV C-163/16)

In Louboutin, the ECJ went beyond the uncompromising opinion of the ECJ advocate general: “According to Advocate General Szpunar, a trade mark combining colour and shape may be refused or declared invalid on the grounds set out under EU trade mark law. The analysis must relate exclusively to the intrinsic value of the shape and take no account of attractiveness of the goods flowing from the reputation of the mark or its proprietor.” (See Figure 3.)

Notwithstanding this, the ECJ stated that it cannot be held that a sign consists of a shape “where the registration of the mark did not seek to protect that shape but sought solely to protect the application of a colour to a specific part of that product… a sign, such as that at issue in the main proceedings, cannot be regarded as consisting ‘exclusively’ of a shape, where, as in the present instance, the main element of that sign is a specific colour designated by an internationally recognised identification code.”

Lego 3D EU trademarks

The path of Lego Juris A/S to obtain registration for 3D trademarks is composite.

In various proceedings with drastically different outcomes, the 3D trademark registration of certain product shapes (see Figures 4 and 5) are helpful for understanding the main issues regarding the refusal of Lego bricks as a 3D trademark.

Ruling on the validity of Lego bricks as 3D trademarks, the ECJ found that “the mark consists exclusively of the shape of the goods”. Evidence submitted of the patents filed in connection with

the functionality of the bricks was not particularly helpful for Lego.

On 30 July 2004 the Cancellation Division declared the mark invalid with respect to construction toys, finding that it consisted exclusively of the shape of goods which was necessary to obtain a technical result.

It stated that “an objection raised under Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation No 40/94 cannot be overcome on the basis of opinion polls or surveys, since, as is apparent from Article 7(3), proof of acquired distinctiveness in consequence of use does not render the sign examined non‑functional”. The Grand Board of Appeal also stated that “a shape whose essential characteristics perform

a technical function does not escape the prohibition on registration if it contains a minor arbitrary element such as a colour”.

Five years later – and involving almost the same issues (construction toys) – the outcome of the proceeding before the ECJ took a drastically different direction with regard to the validity of a 3D EU trademark composed of a Lego figure.

Deciding on trademarks that consist exclusively of the shape of goods necessary to obtain a technical result, the ECJ had a clearer vision in connection with the Lego figure: “By the terms ‘exclusively’ and ‘necessary’, that provision ensures that solely shapes of goods which only incorporate a technical solution, and whose registration as a trade mark would therefore actually impede the use of that technical solution by other undertakings, are not to be registered.” (14 September 2010, Lego Juris v OHIM, C 48/09 P, ECR, EU:C:2010:516, paragraph 48.) “None of the evidence permits a finding that the shape of the figure in question is, as a whole, necessary to obtain a particular technical result. In particular, there is nothing to permit a finding that that shape is, as such and as a whole, necessary to enable the figure to be joined to interlocking building blocks. As the Board of Appeal essentially noted, the ‘result’ of that shape is simply to confer human traits on the figure in question, and the fact that the figure represents a character and may be used by a child in an appropriate play context is not a ‘technical result’.“ (Paragraph 34.)

Conclusion

Although extremely rewarding, it is a challenge to protect non-traditional trademarks and 3D features as EU trademarks. However, seeking protection for signs whose appearance differs from the typical shape in that particular sector provides the basis to allege distinctive character.

In addition to distinctiveness, having at least an element of non-strict functionality would enhance the probability of avoiding the technical objection regarding “the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result”.

June/July